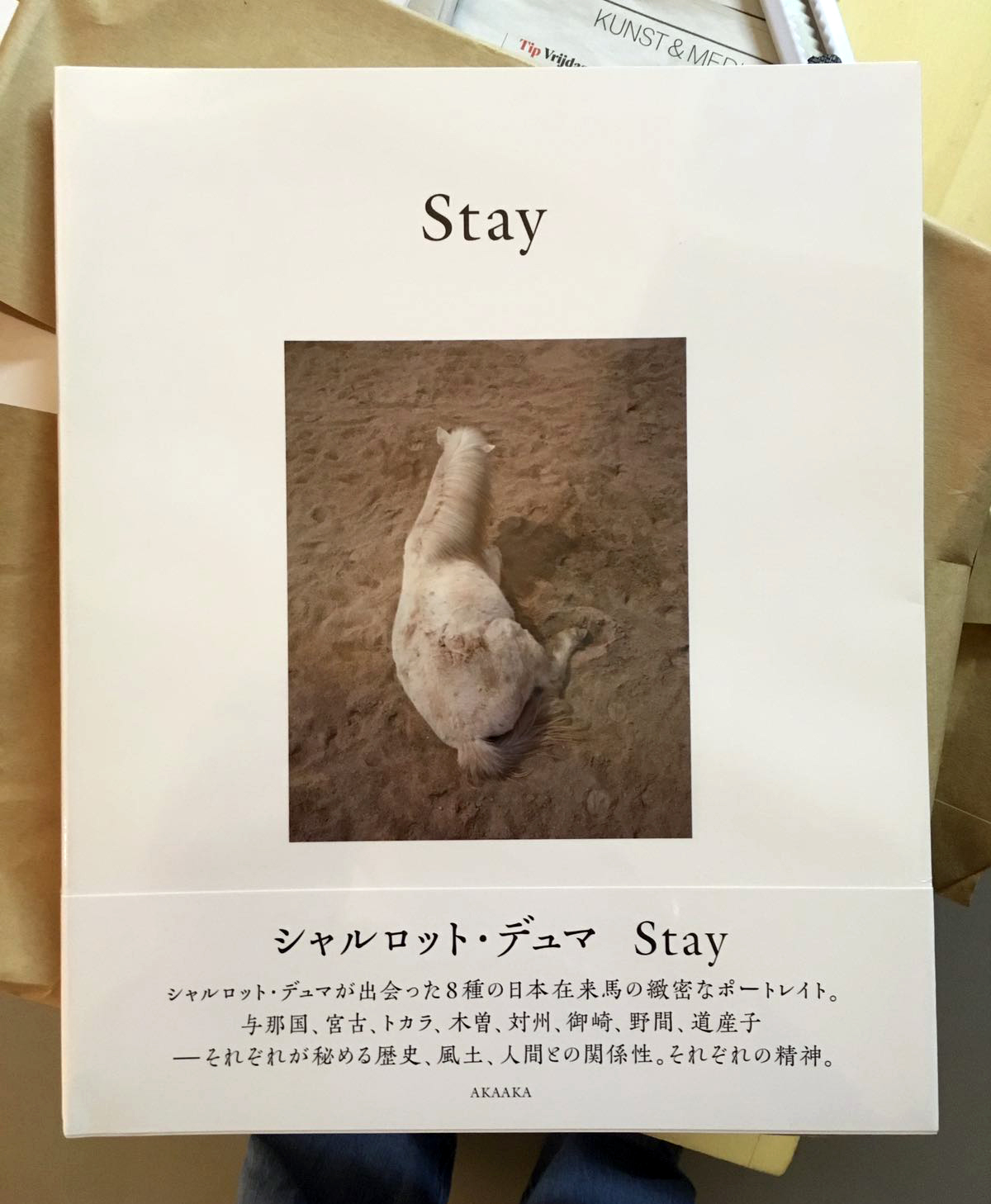

Stay, 120 pages € 35,-

With texts ( English/Japanese) by Eric Himmel, editor in chief Abrams Books NYC and Stacey James Clarkson art director Harper’s Magazine NYC.

You can order the book here or contact 916press

In November 2014 I visited Nagano, on the Japanese island of Honshu, where the Kiso horse, native to the Kiso Valley, is employed in logging. Of the eight indigenous Japanese horse breeds, seven are endangered, and there are only about 160 remaining Kiso horses. Thanks to Nicol, I found myself in Kisofukushima, high in the central mountain range, where Takeru Kanagawa runs the only farm preserving them.

From there, I started researching the other indigenous breeds, each with its own particular characteristics and history and each identified with a different locale in Japan, and gradually a photographic project – a journey to Japanese horses in their homelands – began to take shape in my mind.

After meeting the Kiso horses, which are the largest of the eight breeds, I was mesmerised when I encountered Yonaguni horses, with their tiny frames and their ancient and almost mythical features. They are “stuck” on Yonaguni Island, a tiny Japanese island only 100 kilometres from Taiwan, where they were brought by boat some centuries ago, and their bloodlines are pure. It was early morning, and I was impressed by the way they stood erect and resilient in the aftermath of a great storm that blew over the island the first night of our arrival.

I like being able to come close to animals, to study them for the mysterious “other” they are to me, and I enjoy having to rely on my own instincts and intuition to be able to achieve this. Of course, they are always aware of my presence. Since I mostly try to make portraits, a mutual acknowledgement is necessary. The distance between me and my subject is literally what defines the intimacy of each portrait. Everyone has their own parameters that define a comfortable distance of approach, and with animals you can’t easily override them.

Observing the horses, I find that rest makes up a great part of their days and nights. They snooze a lot when they are not grazing. They like to stand still at given times in the day. They might keep the same positions for up to an hour. I have the impression that they’re reflecting or maybe communicating with each other. It’s a magical moment, when I feel accepted as part of their circle. It might be what ultimately I am drawn to the most, and what I am seeking to capture in my videos.

The semi-wild horses in Yonaguni and Miyazaki reminded me a lot of the wild horses in Nevada. They are looking after themselves and have an air of independence. Visiting all the breeds in their ancestral environments was a kind of pilgrimage, a geographical journey that, through their lives, reveals aspects of Japan’s landscape.

But I’m not sure these horses will have a real future. In most situations they are fulfilling the role of a living monument. Not to trivialise them, but they will never be used again as they were in the past. However, some of the breeds play an important role within Japanese culture. The Kiso had a turbulent past as cavalry horses. The Dosanko horses in Hokkaido are the most numerous, with a population of around 2000. They are not endangered, and they might eventually become Japan’s national horse, like the Friesian horse in the Netherlands or the Camargue horse in France.

Fortunately there are always people who will take an interest in a species that is in danger of disappearing. Likewise with endangered skills: an old horse handler in Hokkaido demonstrated how logs are tied on to the backs of Dosanko horses. This technique became necessary when an ancient law prohibited the use of wagons. It only takes one person to learn this skill to teach another. It’s a hopeful reminder to me that small actions can have great consequences.